Iwo Jima Book Excerpts

Excerpts from Fighting the Unbeatable Foe

Table of Contents of Fighting the Unbeatable Foe

- The Unseen Enemy

- A Marine Grows in Manhattan

- Understanding the Evils of War

- Routine Combat

- Lying Next to a Bundle of Explosion

- Show a Burning Determination

- Kublai Khan Failed to Invade Japan

- A Greater Shock than the Bombing

- A Marine Defends Los Alamos

Summary: Hudson's Story

Bill Hudson hoped he’d see some action before World War II ended. He was a good swimmer, could shoot, and enjoyed explosives, so the United States Marine Corps put him through an early version of SEAL training. Then they gave him a gun, made him an infantryman, and spent months training him to invade an island: Iwo Jima. The island, they told him, would be easy to take. It was fewer than ten square miles and had been bombed for weeks. After quickly taking Iwo Jima, the Marines would move on to Okinawa, setting the stage for the coming invasion of Japan. Hudson landed with the first wave of invading troops. He thought he was prepared for his first day of combat.

Nobody was prepared for the Battle of Iwo Jima, a battle unrivalled in the history of the Marine Corps. The Marines had overwhelming numbers, but the Japanese were prepared. Watching from caves, tunnels, and mines, the Japanese laid their traps, resolved to die rather than surrender. Each one vowed to take ten Marines with him.

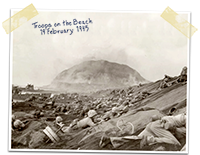

As Hudson and thousands of his fellow Marines invaded the apparently barren island and struggled across Iwo Jima’s coarse, loose volcanic beach sand, a flare went up . . . and the Japanese opened up with everything they had. Every Marine on the beach was a target. Amid the noise, smoke, death, and destruction of that first day, Hudson’s company lost all of its officers.

The battle didn’t end there. There was a second day and a third day and a week and another week. The Marines moved forward at the pace of a snail. Generals and admirals kept declaring the battle over and the island secure, but the Japanese shooting at Hudson disagreed. Battle continued for over a month.

Hudson swiftly discovered that battle was not as it appears in movies and adventure books. Battle was work, gruesome and difficult work, exhausting in every way. Yet he knew there would be an end to the battle, and he hoped to live to see it. Hudson learned not only how to kill, but also how to survive and lead others. He learned the difference between courage and stupidity. His sergeant was a living example of the uncommon valor Iwo Jima was famous for, and his battalion commander received the Medal of Honor.

But his enemy also acted fearlessly. To Japanese soldiers, life was unimportant compared with victory. They had an unconquerable fighting spirit and couldn’t be beaten, only killed.

This is Hudson’s story. This is war—war as his generation experienced it. War was not an occasional job for volunteers; it was the goal of his life for the full “duration of national emergency.” War was a life and death struggle of soldier against soldier, nation against nation. Sacrifices had to be made, sacrifices that may seem senseless to generations raised in easier decades. Through his story, Hudson explains these sacrifices. He speaks to those who are the age he was in World War II. He shows them the realities of a war in which both sides find they are fighting an unbeatable foe.

Book Excerpts

The Invasion

Ready for his first battle, Hudson jumped out as soon as he felt the thud of the amtrac going up on the beach. A mortar shell landed several feet away and hit his platoon sergeant, Mike Schrock, and his corporal and assistant rifleman.

Struggling across the beach, Hudson saw a big flare go up in the sky, and, as he later put it, "all Hell broke loose."

The noise was deafening, and the beach was full of smoke, devastation, wounded, mangled, and dead Marines. It was the most horrible sight I had ever seen in my life.

Hudson

Born and raised in peacetime, young William Hudson, Jr. admired the Marine Corps. Marines were tough, which was good, because he wanted to fight.

Hudson, only sixteen, heard about Pearl Harbor after a football game. He thought the war would be over before he was old enough to fight.

His father wished him luck and hoped the war would end soon. Hudson wanted the war to be over too, but said, "I hope I can see some action after I enlist.”

I am proud that I will be a Marine as long as I live.

Hudson's training, an early form of SEAL training

We went down about sixty feet and just wandered around the bottom and keeping in contact with the man on top. Each of us were down for fifteen or twenty minutes and it is the loneliest feeling in the world.

We were in the surf placing charges and getting ready to knock out the nine blocks. We use five twenty-pound packs of Tetratol on each block and we carry the explosives in our boats. We connected on our charges, etc., and all the necessary steps of demolition work, got out to a safe place and bingo, concrete was flying around like mosquitoes at night.

Why Iwo Jima

The goal of the fighting was to take the only airfield between the Mariana Islands and Japan. Whichever side held Iwo Jima held a great advantage. Sun Tzu called such places contentious ground: ground that attracts battle. Because of B-29s, Iwo Jima was literally to die for.

Another B-29 crew, knowing they wouldn’t make it to Tinian, found that half an airstrip was far better than the sea. Aircrew were desperately glad for Iwo Jima, and at least one pilot named his plane for the Marines.

Yet Iwo Jima would still be unknown if the airplane had been invented twenty years earlier or later.

Leadership

Note:Manuel Martinez was interviewed for the 70th anniversary of the Mount Suribachi flag-raising. Martinez survived unwounded all 26 days of the battle and is still Bill Hudson's hero.

Since all the officers had been killed or wounded in the first few hours of battle, Hudson’s sergeant, Manuel Martinez, led the platoon. Martinez had appointed himself leader for lack of anyone with higher rank, and also because he was a natural leader who knew what he was doing.

War rarely has the drama of a film. A combat team of movie heroes would soon be dead, because battle requires caution. For a team to survive, most of its the men have to do their duty without doing anything too crazy. But the team must also move, and there isn’t much motion if each man only does his duty. Someone has to be aggressive, ignoring his own safety, daring others to move forward.

[Fourth Division Commander General] Cates understood heroic fighting. As a lieutenant at Belleau Wood in World War I, Cates had become famous for reporting that with most of his men gone, lacking support, and under constant fire, he would hold.

The brotherhood of battle

We waited for the Japs to come again that night, and during the hours of darkness when it’s cold and you are scared, you talk to your buddies and you seem like brothers to each other, because of the intimacy and warmth of knowing you have a friend who has saved your life and guards you while you sleep in a muddy hole that’s not even fit for the land crab that shares it with you.

In my whole life I never had the experience of being with a group of men who were so close, so devoted, so dependable, so brave, and so afraid.

War

War is not Hollywood. For instance, you don’t fall on a hand grenade, you throw it back. You hide from it. You tell your other buddies to hide from it. War destroys hopes, dreams, and people, especially young men. War is also part of the history of the world; all of history holds only short periods without war.

The Japanese defenses

As the Marines moved inland, the tunnels, caves, and crevices left them confused about where the enemy was and how many there were. When Marines approached, the Japanese could shoot, disappear through the tunnels, and then reappear behind the Marines.

Japanese discipline impressed the Marines. The Japanese were good, they said, though Marines were better.

Overwhelming force versus indomitable spirit

Americans greatly outnumbered Japanese—this was war, not a fair fight. The saying among soldiers is: if you’re in a fair fight, you didn’t plan it well enough. But the Japanese defenses and their will to fight mattered more than numbers.

Certain defeat was no reason to quit. Japan’s premier announced the loss of Iwo Jima by radio, telling listeners to show 'a burning determination' to defend Japan. He told them there would be no unconditional surrender; the last living Japanese must fight until the enemy’s ambitions were shattered.

Even after Iwo Jima was officially lost, the Japanese left there kept fighting. Many expected to win as soon as help arrived.

The ferocity of the battle

After a week, the Japanese still held three-fifths of the island.

The casualty rate of some infantry regiments reached 75%, leaving very few Marines who fought the battle from start to finish. There were very few Japanese left at all.

The Fourth Division, with Bill Hudson, moved less than a hundred yards some days. Over twenty-six days, the division landed on the right side of the beach, headed north, and later swung around east, to finish on the northeast part of the island. Hudson’s unit traveled a mile or two during this time, moving on average ten or fifteen feet per hour. A snail could have crossed Iwo Jima with them.

Iwo Jima was a 'perfect' battle: expected by both sides and fought over a well-defined area—military force against military force in a barren landscape, with no civilians to complicate matters.

Rest and Hygiene

Toothbrushes were not for teeth, though Hudson did brush his teeth during the battle at least once.

Many matters of appearance and hygiene took second place to survival. During his time on Iwo Jima, Hudson never shaved and never changed his underwear, socks, or clothes.

We usually sleep an hour and watch an hour and no matter how much noise is going on you can always sleep when it’s your turn because you are so tired.

Faith

Iwo Jima was a shock to faith; not all faiths withstood the shock and the fear of death and what lay beyond.

Los Alamos

After all, these were foreigners talking about an atom bomb, which was science fiction—like space travel. And they came from Europe. Could they really want to build a bomb to use on their own countries? The answer was yes: a bomb would destroy less of Europe than Hitler would, and the refugees feared what Heisenberg’s team might build for Hitler.

Arriving scientists were sent to a small office in Santa Fe, which arranged for famous physicists to get to Los Alamos under assumed names. “Nicholas Baker” was the Nobel Prize-winning Danish scientist Niels Bohr who developed the Bohr model of the atom. Enrico Fermi, as in the element fermium, was Eugene Farmer.

Nearby were the ancient trails and ruins of Bandelier National Monument, where scientists hiking with Niels Bohr had to warn him that skunks—unknown in Europe—should be left alone.

The original Los Alamos was the physics version of creating a football team from everyone in the Pro Football Hall of Fame; thirteen Los Alamos scientists had already been or later would be awarded the Nobel Prize for physics.

Decision to use atomic bombs

Since Iwo Jima, American concern had grown over how many Americans were dying in the war. The Joint Chiefs of Staff wondered how to tell the nation the losses were only beginning.

Nobody had invaded Japan since Kublai Khan had failed spectacularly against the storm the Japanese called a divine wind, or kamikaze.

One B-29 went with them to Iwo Jima, then stayed there on standby. If the Enola Gay had trouble, Tibbets could land on Iwo Jima and move the bomb to the other B-29, using the bomb-transfer pit dug near Mount Suribachi.

Maybe the Americans did have an atomic bomb. But probably just one, or just a few, Japanese leaders decided. All Japan had to do was endure.

But on Tuesday, 14 August 1945, Emperor Hirohito surrendered, announcing his decision the next day by radio to Japan. His subjects had never before heard the voice of their emperor god. This was the decisive “Stop!” and it was necessary, since even in Hiroshima’s hospital, filled with the dying, anger broke out at the thought that the war had been in vain.